The Limits of Autonomy: Technology, Nihilism, and Giving a Damn, Part I

What's really at stake in our increasing deference to AI systems? Individual autonomy is only part of the answer. Care gives substance and direction to autonomy. Autonomy gives form and force to care.

AI’s Paradoxical Dispensation

Generative AI puts us in a paradoxical condition. Here is one aspect. These technologies endow us with enormous new creative and productive capacities, even in domains where we are utterly incompetent. Without any specialized training we can prompt AI to create computer programs, websites, images, texts, games, videos, songs, and more.

At the same time, these technologies enter our lives in a much more personal way: with some people turning to them for companionship and therapy, as well as advice and direction in various aspects of life, from trivial everyday choices like what to cook to existential questions of relationship, career, and identity.

Autonomy and the Dangers of Algorithmic Deference

The lures into algorithmic dependency are intensifying. There is evidence that today we are moving beyond the mind-numbing “attention economy,” where technology companies compete to harness and fragment our attention, into a soul-sucking intention economy. Major AI companies are aiming to draw us into such intimate relationships with their AI chatbots that they can directly captivate and commodify our very intentions for engaging with the world.

This latter range of temptations has been the subject of a series of thought-provoking blog posts and videos from the folks at Cosmos Institute. The Cosmos Crew has been vigorously raising the alarm about a dire threat they see in an expanding personal deference to AI: a forfeiting of our capacity to deliberate and choose the path of our own lives, an atrophy of our powers of autonomous agency.

See, for example the Cosmos Institute blog posts, “In Defense of Self-Direction,” “Is algorithmic mediation always bad for autonomy?” and “Live by the Claude, Die by the Claude.”

In the last-mentioned piece, Brendan McCord, founder of the Cosmos Institute, comments on the vexing eagerness of some users to voluntarily surrender their own intentions to AI, looking to ChatGPT or Claude for constant instruction on how to live.

McCord has thus been warning of the gradual onset of an insidious “autocomplete for life” where AI is continually “suggesting not just our next word, but our next action, job, relationship, purpose” and thus decisively diluting our personal autonomy, our capacity for deliberative self-direction.

This range of concerns was also at the center of a Cosmos Institute-Liberty Fund Seminar on “AI and the Future of Human Autonomy” that I enthusiastically attended in London back in June. The thoughts I’m sharing here have been brewing since then:

The most recent intervention from the Cosmos Crew on this front is an in-depth and worthwhile conversation between Brendan McCord and Johnathan Bi:

In a social media post announcing the conversation, Bi writes:

The real risk of AI isn’t extinction, it's being turned into NPCs, into mindless sheep . . . One of my friends uses ChatGPT for hours every day not just as a search engine but as an operating system of his life, he asks it: - Where he should eat - What he should text girls on dating apps - He gets up every day and has it create a schedule for him.

My friend does this not because he’s stupid, he’s one of the smartest people I know, but because ChatGPT already knows so much about him that the advice is getting quite good. The restaurants and shops it recommends for example are already better than ones he can find himself.

My friend is not alone. Gen Z & Gen Alpha are increasingly using AI as a holistic operating system to which they offload their own decisions onto. And [Brendan McCord, i.e., @mbrendan1] argues that this kind of offloading is the real danger of AI no one is talking about.

NOTE: It is not clear how common this LLM-as-life-OS actually is at the moment. Neither of two fresh usage studies (from OpenAI/NBER and Anthropic) track it. The OpenAI/NBER paper does report that 29% of overall usage of ChatGPT falls under the category of “practical guidance,” which includes many kinds of queries that might worry Cosmos: “How-To Advice, Tutoring or Teaching, Creative Ideation, Health, Fitness, Beauty, and Self-Care” (boldface mine). Nevertheless, even if such life-off-loading is still marginal and mostly anecdotal, the ethical and existential stakes are real and worth exploring.

When Autonomy Doesn’t Matter

But McCord and Bi are overlooking important elements of the background to their central concern. The dilution of interest in individual autonomy that they have noted among younger swaths of the population doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Or rather, it does happen in a vacuum: a vacuum of existential meaning in our technological age.

Algorithmic saturation and the cult of optimization are symptoms of a larger historical context, one endangering our ability to live meaningful lives in pursuit of what we care about.

Witness the propensity among young people today to self-identify as nihilists, and to experience themselves as thrust into a life that has no, or very few and out of reach, possibilities for meaningful involvement; or even, per the 2021 book The Sunny Nihilist, to see the promise of meaning itself as just a ruse to inure them to the pressures of “endless optimization” and competitive status-seeking.

(In a forthcoming sequel to this post, in the section called “A Deeper Diagnosis of the Nihilism of Our Times,” I will connect the description of Millennial and GenZ nihilism in this section to Martin Heidegger’s understanding of the nihilism of our technological age.)

The roots of this rising tide of nihilism go even deeper than the disastrous effects of smartphones and social media on the self-esteem and psychological wellbeing of young people as reported by Jonathan Haidt in The Anxious Generation.

A viral 2020 BuzzFeed article called “Generation Free Fall” (and discussed in The Sunny Nihilist) helps to frame what’s going on. It profiles nine Millennials and Gen Zers in the midst of the Pandemic about their generation’s sense of perpetual crisis and generalized existential dread. The avowal of one of the 21-year-olds featured in the article, Hailey Modi, is emblematic:

“We grew up in a world where things have already gone terribly wrong and our lives are just preparing for the worst.” (From “Generation Free Fall”)

Kyla Scanlon, an intensely thoughtful denizen and voice of Gen Z, puts it like this:

Gen Z and Millennials are the first generations to truly be nihilistic. The loss of religion, the extreme polarization, constant news flow blah, blah- we are all familiar. It creates a sense of “lmao okay, what is going on” that translates widely to massive disillusionment with a system and the suffering that takes place within that system . . .

Because there is a void of community, because we are trying to calibrate to suffering, because we are waiting for a marshmallow, but waiting is the actual dystopia. We have misplaced outrage that we turn into consumption of videos about Fake Karens. We get behind people selling a newsletter subscription about how the world is going to end.

(See Kyla’s Newsletter, “Fragmentation, Polarization, and the Marshmallow Test”)

Here is Scanlon again, further articulating the sources of today’s nihilism:

Politics is a game show. Reality is entertainment. Baudrillard watches with intensity. The panopticon of observation. Vulnerability is our greatest asset and our greatest risk.

The youth are growing up in a time of political minefields. Their attention spans are destroyed, but that is because the youngest generation is exposed to 30 different things from gut wrenching to wonderous in the span of 1 minute.

The constant scrolling tells us that nothing is worth remembering, nothing is worth reflection, nothing is worth production because the act of consumption is simpler.

If you just keep scrolling, maybe that weird disjointed feeling will finally go away.

(See Kyla’s Newsletter, “Gen Z and Financial Nihilism,” boldface mine)

Gen Zers also find themselves mired in a depressing economic context that they experience as a badly broken promise of the formerly sacred American Dream.

Here is Scanlon in her recent conversation with Ezra Klein:

Because it’s like: What is next? What does this mean? I think part of it is the broken-ladder problem: So you graduate from college — do you get a job?

Twenty-three percent of Harvard M.B.A.s were unemployed three months after graduation. Those are the cream of the crop, right? If they can’t find jobs, then it might be tough for you.

You see all this data, and you’re wondering what it means for you with housing and career progression. Because people are taking longer to retire.

I think all of those points can create that feeling of hollowness: What is it all for?

On top of this, young people are being told by a constant flow of AI hype out of Silicon Valley (and also in the mainstream media) that AI will take over most jobs within their lifetimes. Hype aside, early evidence suggests AI use is slowing hiring for junior roles.

The experience of hollow disorientation and disaffection in young people articulated by Kyla Scanlon and books like The Sunny Nihilist help make sense of why some might be tempted to turn to AI for constant guidance, companionship, therapy, and even— tragically — advice on how to die by suicide.

In an experiential-historical context where, in Scanlon’s words, “nothing is worth remembering, nothing is worth reflection, nothing is worth production,” there is little motivation to take the reins of life autonomously into one’s hands. Finding no goals or bigger purposes worthy of connecting with and striving towards, one finds nothing worth doing.

Remember, the root word for nihilism is the Latin nihil, which means nothing.

Nihilism as the Atrophy of our Capacities to Care

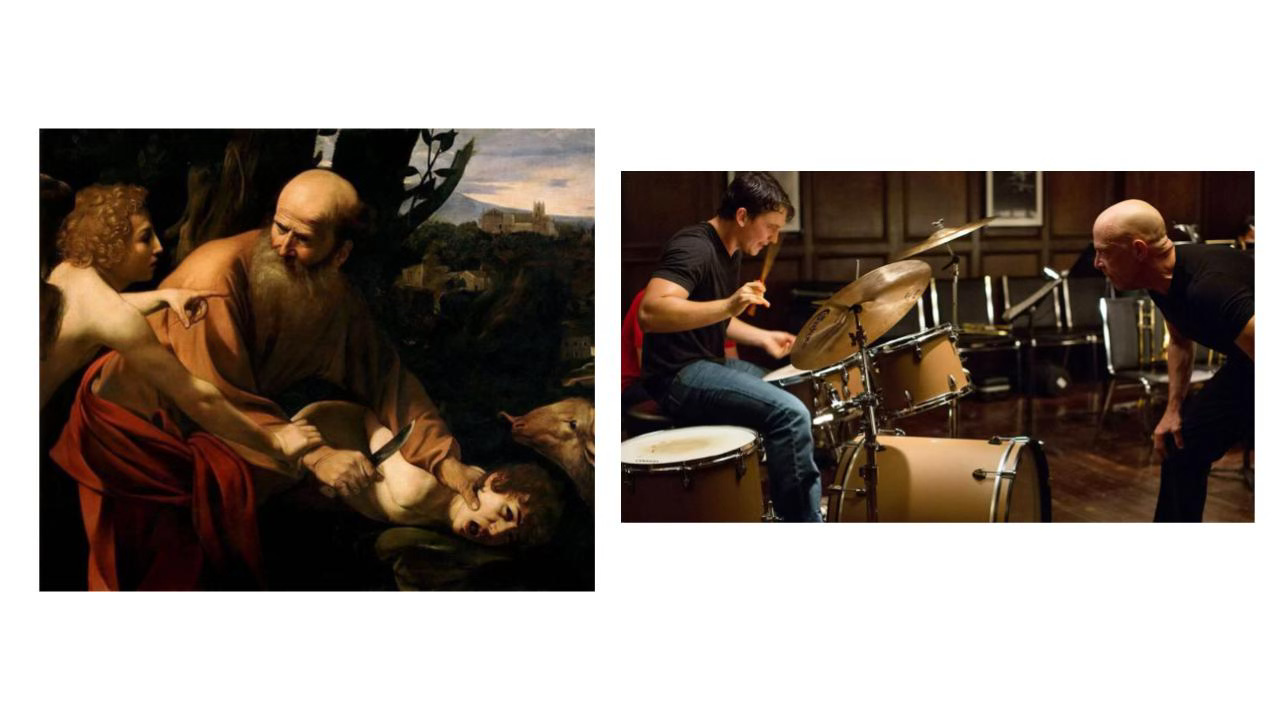

The sense that “nothing is worth doing” reveals a withering of the capacity to care. The central feature of the capacity to care is being able to attune to and identify yourself with meaningful projects that you care about for their own sake—things you do and relationships you maintain because they call out to you as important and solicit your love and attachment, rather than because they get you some further thing or status or optimize your further options.

With a withered capacity to care, autonomy (the capacity for effective deliberation and free choice) is empty, lacks substance and direction.

As Harry Frankfurt, one of our best philosophers of care, puts it:

“If we had no final ends [i.e., projects and purposes that we care about for their own sake], it is more than desire that would be empty and vain [per Aristotle]. It is life itself. For living without goals and purposes is living with nothing to do”

(Frankfurt, “On the Usefulness of Final Ends,” in Necessity, Volition, and Love, p. 84. Boldface and brackets mine.)

My point is this: If we fixate on individual autonomy and choice while ignoring meaning-making and care, we miss what’s at stake as algorithms mediate more of life.

Note: When pushed by Johnathan Bi during their conversation, Brendan McCord acknowledges that autonomy is necessary but in and of itself insufficient for human flourishing. I come back to this part of their conversation below, and in one of the forthcoming sequels to this piece.

What people need in order to avoid becoming mindless sheep and NPCs, in Johnathan Bi’s phrase, is not just more experience with autonomy and free choices, it is a revitalization of their capacities to care and to take care of what matters, that is, a revitalization of their capacity to be receptive to and affected by concerns and issues that call out to them as important and worthy of their commitment, beckoning their involvement in life, even in the midst of an otherwise grim-seeming, nihilism-inducing situation.

Autonomy calls to be lived in the midst of care.

See my post “Notes on Care” (With David Spivak) for more on care.

The Connection between Care and Meaning in Life

A meaningful life is one lived in connection to and service of relationships, projects, and causes that matter for their own sake, not because they help obtain some further reward or serve some other purpose (like advancing our status or earning us money or opening up other options).

A meaningful life is one lived in contact with and development of what we care about; something we feel claimed by and drawn to attend; something that exceeds us and our individual choices and desires, putting us in touch with a bigger context; lending, for a time, coherence and continuity to our lives.

As usual, in the context of a discussion about care, I always find myself quoting one of my main mentors about the role of caring in human life, the nurse Patricia Benner (who was also a student of Hubert Dreyfus).

Caring is having something to do, being moved to tend to what matters, the matters that make someone who and what they are and bind them to the world.

I appreciate Benner’s emphasis on how caring can lead people into “a wide range of involvements, from romantic love to parental love to friendship, from caring for one’s garden to caring about one’s work to care for and about one’s patients.”

In my life, one of the things I’ve cared deeply about, having been consistently guided by and grounded in, is my love of drumming and being in unlistenable punk bands: not a particularly rational form of activity!

(See here and here for some of my philosophical inquiries into the essence of punk and its connection to nihilism.)

Care gives substance and direction to our autonomy. Autonomy gives form and force to our care.

The Full Scope of Human Agency

Brendan McCord and the Cosmos Crew emphasize the need to use our powers of deliberation and free choice, lest these powers be usurped by external systems and become dissipated from disuse.

But what we love and deeply care about—what fundamentally matters to us—is itself not a matter of free choice or decision.

The experience of care is the experience of a kind of necessity that guides and structures our choices. We feel compelled by or drawn to something or someone, sometimes irresistibly, but we experience this as an expression of ourselves and our freedom, not as a thwarting of ourselves and our freedom. Of course, this is why we talk about falling in love. Harry Frankfurt again is useful on these issues:

“What we love is not up to us. We cannot help it that the direction of our practical reasoning is in fact governed by the specific final ends that our love has defined for us” (Frankfurt, The Reasons of Love, p. 49).

Elaborating with characteristic, compelling clarity on the disconnect between care and choice, Frankfurt writes:

“A decision to care no more entails caring than a decision to give up smoking entails giving it up . . . This would hardly be worth pointing out except that an exaggerated significance is sometimes ascribed to decisions, as well as to choices and to other similar ‘acts of will’. If we consider that a person’s will is that by which he moves himself, then what he cares about is far more germane to the character of his will than the decisions or choices he makes. The latter may pertain to what he intends to be his will, but not necessarily to what his will truly is.”

(Frankfurt, The Importance of What We Care About, p. 84).

Now, our decisions and choices do play a role in how we go about actively taking care of what matters to us and effectively involving ourselves with it. There is an important truth in the Cosmos Crew’s celebration of autonomy. The full picture of a meaningful, autonomous life involves living in the tension between the receptivity to what matters and calls us as important, and the activity of responding to and effectively tending to and taking care of that.

I explore the balance and tension between the receptive and active dimensions of human agency in my scholarship on the philosophies of Harry Frankfurt and Martin Heidegger. See my paper, “Care, Death, and Time in Heidegger and Frankfurt,” or the much more extended discussion in my doctoral dissertation, Thrown Projection: An Interpretation and Defense of the Hermeneutic Conception of the Self in Heidegger’s Being and Time, “Part III: Receptivity and Care: Heidegger and Frankfurt on Human Identity.”

In fact, McCord and the Cosmos Crew are on to this. McCord and Bi approach this tangle of issues in their brief comments on religious ways of being, and how some people are drawn to actively “surrender” themselves to Christ. I’ll return to this phenomenon next time, because a secular variation on such an “unconditional commitment” is central to how existentialists like Søren Kierkegaard, Martin Heidegger, and Hubert Dreyfus understand the dynamics of the being a self.

In “In Defense of Self-Direction,” Cosmos also tangentially nods toward receptivity: autonomy needs to be suffused with what matters.

“Agency without autonomy is hollow: sophisticated choice-execution emptied of genuine purpose. Autonomy without agency is impotence: a clear vision of what matters but no power to pursue it."

And:

"To flourish as humans requires more than comfort, efficiency, or the mastery of nature. The greatest goods of human life—friendship, family, wisdom, creative endeavor—cannot be delivered to us ready-made. They must be pursued through self-motivated striving."

This belongs to the core of McCord’s important acknowledgment that autonomy, while being necessary for a life of flourishing, is not itself sufficient for it.

Nevertheless, this dimension of the position being developed by McCord and Cosmos is left significantly under-developed compared to their emphasis on individual deliberation and choice. The critique I am beginning to offer here does not undermine and invalidate this picture, but rather importantly complements and enriches it.

Provisional Conclusions

McCord and Cosmos get it right about something fundamental: we should resist the seductive narrative that AI will, or should, aim at a wholesale replacement of human judgment, gradually taking over the inherently messy business of being human.

How can we imagine and build AI as an amplifier of what makes us our beautifully weird selves: our abilities to care, to make meaning, and to open up and preserve a vast plurality of ways of being in the world, including those ardently irrational, often gloriously inefficient, dimensions of love and care that resist both free choice and technological optimization?

We need AI that strengthens our capacity to care and connect, not merely calculate and choose. And we need the skills and dispositions to welcome these systems in ways that deepen, rather than erode, our plural forms of life. That’s the wager of my Curiosity Craft project and my involvement with Topos Institute in Berkeley.

More coming soon. Thanks for reading!

You can support me by subscribing or leaving a one-time tip. Thank you!

Oh my goodness, what a rich and valuable piece of writing. This line alone had me pause and think for a few minutes... "a vacuum of existential meaning in our technological age."

I am with you in this invitation: "We need AI that strengthens our capacity to care and connect, not merely calculate and choose. And we need the skills and dispositions to welcome these systems in ways that deepen, rather than erode, our plural forms of life." I have just registered for Curosity Craft and will be diving in. Thank you!